Covid Chronicle, part 38

door Diana Ozon

And then it got really quiet.

Last week I was surprised by a phone call from an OBA employee asking which books I love?

What? I missed my OBA. Every week I sat there writing for hours when it got too quiet for me at home, reading my newspapers, wandering along the shelves with the silent books looking for my new gem for home. In Café Belcampo, actually the living room of the library in the Hallen, I met my friends. I enjoyed the people around me, the smell of coffee, the little ones in the play corner, watched at a safe distance by their mothers, fathers, grandmothers and grandpas, who calmed me down when a peeling came up. A wet nose knew whether the first impulse was for that rather difficult little puzzle car. And if, after an afternoon of all those heartwarming impressions, I still didn’t feel like going home, I picked up a film in the Hallen or wandered around the market in the Kinkerstraat for a while. The food afterwards, in my quiet house, tasted so much better after my little trip through Amsterdam-West.

And then it became really quiet.

The doors closed. One after the other. On the large entrance gate to the passage of the Hallen I found a wet rained letter telling me in hasty words that you could find the bicycle mechanic on good luck via a hindsight route. The bicycle shed, underneath the buildings, was still open, but what for? In the colourful shop windows of the clothing shop right next to the closed entrance gate to the Hallen, an A4 sheet of paper had been stuck with the changed opening hours. The cocksucker’s feet seemed to be a cry for help, an entrance door was missing, forgotten behind the closed gates of the Hallen.

Which books do you like?’ asked the friendly voice on the other side of the line again.

I realized I didn’t know that. I never looked for books, I always found them. I touched them with my eyes before my hand went the same way, judged the spine, a title, became fascinated by the font. I was made curious by the icon on the back, took historical while being more of the contemporary. I touched them and the books chose me, like I once went to a shelter for a dog and came home with a cat that didn’t want to leave my side.

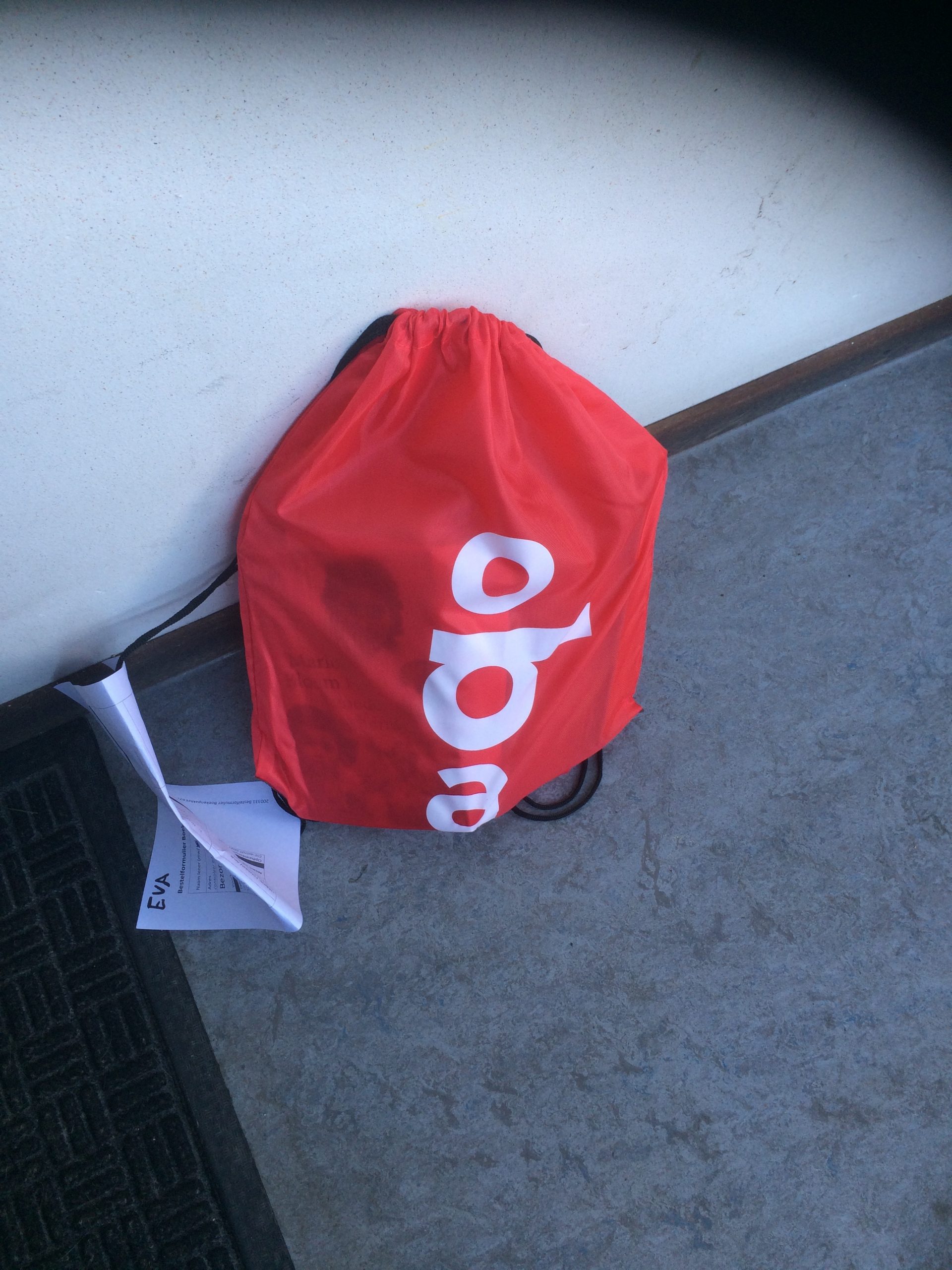

And today he was at my doorstep, the boy from the OBA. Five high. The agreement was that he would put the five books at one and a half meters from my door and that I would put my books, which had long since passed their lending period, in a white pastic bag in the same place.

The elevator made its familiar sounds. I heard the cables, the elevator door opening and closing a few times, the metal running board always rattling after every stir. I counted the floors. It seemed more than five.

On the threshold of my house I waited with the plastic bag still in my hand. Something kept me from putting the books on the floor, in a cold hall far away from me.

And there he was, a young man with a tanned head and a radiant white smile looking around the corner. Skittishly, though, as if he wanted to run away from something. His smile was unforgettable. Why he forgot his assignment, I don’t know? And I’m not sure if two outstretched arms are a meter and a half either, but we’ve reached each other, the heartwarming red bag, with the so familiar white letters on it, and me. At the ends of the black cords dangled like a dead butterfly, a white described sheet. The delivery date was remarkably large, May 4, 2020 – commemoration of the dead on an empty Dam Square it shot through me. And the pick-up date? “This will be filled out later” I read.

For the first time in seven weeks I cried.

by Maria Es